[ad_1]

As advanced drone operations scale, stakeholders need greater understanding of ground-based surveillance systems (GBSS) and airspace awareness tools that enable autonomous, BVLOS operations: and the terms that describe their coverage relative to drone operations. Here, an expert from MatrixSpace explains Surveillance vs. Declaration vs. Operational volume. MatrixSpace is re-imagining radar, addressing the next generation of AI-enabled sensing so that objects can be identified and data collected in real-time.

The following is a guest post by Akaki Kunchulia of MatrixSpace. DRONELIFE neither accepts nor makes payment for guest posts.

A Primer: Surveillance vs. Declaration vs. Operational volume for UAS

By Akaki Kunchulia, Airspace Regulations, MatrixSpace

There’s a common misconception in the UAS industry when talking about surveillance and operational volumes for UAS operations. The RTCA DO-381A Ground-based Surveillance System (GBSS) Standard provides definitions for these terms:

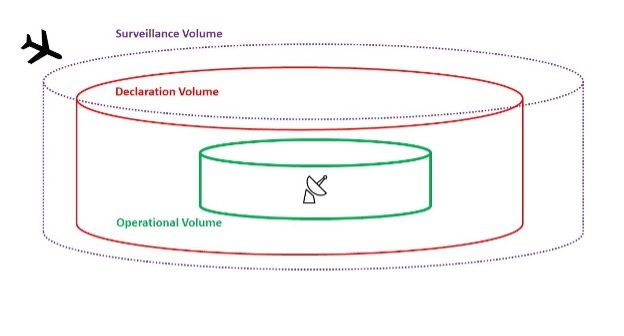

- Surveillance Volume is the 3D volume defined by the area where at least one Ground-based Sensor (GBS) has coverage.

- Declaration Volume is the 3D volume inside the Surveillance Volume where at least one sensor meets the track accuracy requirements and can declare the track for air traffic.

- Operational Volume is the 3D volume where the UA relaying on GBSS track data can safely operate within its performance specifications.

While these terms sound a little confusing, let’s try to make them more comprehensible.

While these terms sound a little confusing, let’s try to make them more comprehensible.

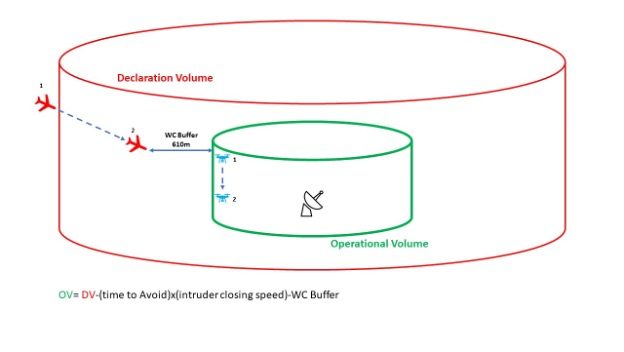

Imagine that an air traffic intruder (big/small plane, helicopter) flies towards the GBSS location. The first area it will hit is Surveillance Volume (SV). SV is an area where a ground-based system can detect “something,” but is still not clear if this “something” is a real intruder or some kind of other object. The system is still trying to find out if this object is a real intruder or not. Once the GBSS system passes the criteria for track determination, it declares the object as a track of an air traffic intruder – and the intruder is transitioned from the surveillance volume to the Declaration Volume (DV) (it should be noted that different technologies (e.g., RADAR, Electro-Optical, or Acoustic) have different approaches to determining whether the intruder is an object of interest or not. Each technology uses its own algorithms and techniques to define the criteria for track establishment).

From this point on, the intruder is in the Declaration Volume. The GBSS has established the track and can transmit it to the other functions in the DAA framework, such as Alert or Avoid functions.

The Alert function should now determine if this intruder is a threat to the UAV or not. If the intruder is determined to be on the course to breach a UAV Well Clear (WC) Volume (2000ft horizontal ± 100ft vertical), then an avoidance maneuver is initiated (commonly a vertical descent to a safe altitude). While the UAV is executing this, the intruder is still flying towards the UAV. Once the UAV reaches a safe altitude, a minimum 2000ft (610m) horizontal buffer should be between the UAV and the intruder to ensure that WC volume is not breached.

To determine the Operational Volume (OV) around the GBSS, the UAV operator should take into consideration multiple variables such as the Declaration range, average intruder speed, total avoidance maneuver time, and others. Below is a simple example of how to determine operational volume boundaries based on all of the above:

Let’s assume:

- GBSS Declaration Range – 2000 meters

- Average intruder speed – 57m/s (110 kts)

- UAV operational altitude – 100ft AGL

- UAV safe altitude – 50ft

- Time to complete the avoidance maneuver – 4s (50ft descend at 4m/s descend rate)

- Pilot response time – 5s (Per ASTM DAA performance standard, pilot-directed maneuver)

- Total system latencies – 1s

- WC buffer – 2000ft (610m)

To determine the operational volume radius, we must calculate the worst-case scenario, meaning that the UAV is at the edge of the operational volume, and the intruder is flying toward it.

- GBSS detects the intruder at the 2000-meter range.

- The detected track is communicated to the Remote Pilot In Command (RPIC)

- Pilot executes predetermined avoidance maneuver procedure (5s)

- UAV completes avoidance maneuver and reaches the safe altitude(4s)

- Add total system latency (1s)

- Subtract WC buffer 610m.

If we do “Outside In” calculations >>> 2000m – 5sx57m/s – 4sx57m/s – 1sx57m/s – 610m= 820m. This means that based on the above assumptions, at an 820m radius from the GBSS, the UAV can operate everywhere and have enough time budget to reach the safe altitude when encountering the intruder in a worst-case scenario. If the UAV is operating inside the 820m radius volume, then it will have more time to reach the safe altitude, therefore making the whole operation safer.

The above calculations represent the simplified version of the operational area determination. Actual calculations might take into account other variables.

Conclusion

UAS Operational Volume is not a fixed value. While the GBSS Surveillance and Declaration ranges are fixed, UAV Operational Volume is mostly dependent on the UAS operations conops and the characteristics of the UAS systems. Making adjustments to the operational and safe altitude, UAV speeds and other factors can drastically change the operational area. It’s therefore upon the system integrators to determine the exact dimensions of the operational area based on certain locations and circumstances.

Learn more about MatrixSpace’s drone detection solution at https://matrixspace.com/dronedetection/

Akaki Kunchulia, Airspace Regulations Lead, MatrixSpace has over 18 years of experience in the aviation field, starting his career in the Republic of Georgia as an Air Traffic Controller at Georgian Air Navigation. He has supported the FAA and NASA on multiple programs such as UAS Traffic Management, FAA NextGen, SESAR JU harmonization, and NASA mostly in UAS and Advanced Air Mobility fields.

Akaki Kunchulia, Airspace Regulations Lead, MatrixSpace has over 18 years of experience in the aviation field, starting his career in the Republic of Georgia as an Air Traffic Controller at Georgian Air Navigation. He has supported the FAA and NASA on multiple programs such as UAS Traffic Management, FAA NextGen, SESAR JU harmonization, and NASA mostly in UAS and Advanced Air Mobility fields.

Read more:

Miriam McNabb is the Editor-in-Chief of DRONELIFE and CEO of JobForDrones, a professional drone services marketplace, and a fascinated observer of the emerging drone industry and the regulatory environment for drones. Miriam has penned over 3,000 articles focused on the commercial drone space and is an international speaker and recognized figure in the industry. Miriam has a degree from the University of Chicago and over 20 years of experience in high tech sales and marketing for new technologies.

For drone industry consulting or writing, Email Miriam.

TWITTER:@spaldingbarker

Subscribe to DroneLife here.

[ad_2]